Whether they live in Parkland, Baltimore or Toronto, teens want change

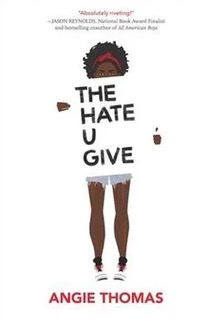

In the first few scenes of The Hate U Give, 16-year-old Starr Carter sees one of her closest friends, Khalil, shot and killed by a police officer. She’ll never be the same. While the world swirls around her in advance of her testimony before a grand jury, Starr fears retribution from a gang leader, defends Khalil on television, speaks through a bullhorn for the first time, and questions every friendship she’s ever had.

Amidst the chaos of riots in her own neighbourhood, Starr is faced with tough choices about how to respond to the injustice of being black and how to honour her friend Khalil’s memory.

Timely message

Gun violence disproportionately affects black kids. This Time magazine article from last year suggests that black kids are 10 times more likely to die because of gun violence than white kids.

Today, as thousands of young people attend March For Our Lives events across North America to protest gun violence in schools, this fact must be front and centre: Black teens have been talking about guns for years. Oprah didn’t offer them $500,000 to support the cause, but they deserve to be heard.

We need to know their stories.

The Hate U Give, which was inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the music of Tupac Shakur, is a great way to open up the conversation around guns and race with the teens in your life.

Breaking down race barriers

Starr is a 16-year-old basketball player and lover of rap music lives in Garden Heights, where her black parents work and grew up. But Starr’s parents abhor the gang violence in Garden Heights, so they send her to private school in another neighbourhood. As a result, most of the kids she hangs out with are white. Even her boyfriend Chris is white.

The white kids won’t visit her at home. The black kids say she acts like she’s “too good for a Garden party” just because her parents won’t let her go out at night. And Starr must constantly tweak her language, dress and mannerisms for whatever social group she finds herself in. It’s exhausting and lonely.

But because she’s been leading this taboo double life in a highly racialized world, Starr offers a unique perspective as a narrator. She sees things from all the angles.

For example, when it comes out that Khalil had been dealing drugs, she knows how that will look if it gets into the media. She also knows the reason he was doing it — to pay off a gang leader who was threatening his mom. And most importantly, Starr knows Khalil’s life mattered — whether he sold drugs or not.

Starr’s view of inter-racial relationships is valuable, too. After Khalil’s death divides everyone, Starr must subtly test her friends to find out if they respect her family and support her activism. Friendship goes way deeper than skin colour for Starr. Chris turns out to be a trustworthy bae and an empathetic guy, so he gets to stick around. But Starr’s former best friend Hailey doesn’t seem to get it, and Starr makes the tough choice to delete Hailey’s number from her phone.

Suspenseful action

Despite Starr’s honest testimony before the grand jury, the police officer who shot Khalil is found innocent of wrongdoing. That sparks riots and looting in Garden Heights, and Starr feels the visceral anger of the mob in her body.

She understands why people feel they have no choice but to resort to violence. But Starr sees a better way. She knows her voice is her most powerful weapon, and when someone holds out a bullhorn, Starr takes it in her hand:

“Everybody wants to talk about how Khalil died,” I say. “But this isn’t about how Khalil died. It’s about the fact that he lived. His life mattered. Khalil lived!”

Nuanced characters

Characters in this novel are not stereotypically “black” nor stereotypically “white.” For example, some black characters speak in a regional dialect while others do not. Likewise, some white characters are clueless about the artistic ascendancy of the ’90s sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, while others are not.

Starr defies everyone’s expectations by stepping up to that bullhorn, and there is tremendous power in her choice. Everyone has a plan for Starr — her parents, her friends, her school, the media, her lawyer — but when she speaks her truth, she takes control of her own life.

Still, while it’s exhilarating to see Starr stand up to power and find her voice, there is nothing fuzzy about the ending of this book. Khalil is still dead at the hands of police. And so are many other young black people, 14 of whom Starr lists as she reflects on her reasons for speaking up.

Starr’s story makes it clear that the burden of activism against gun violence still rests on the shoulders of innocents. We’re leaving it up to people who should be playing basketball, studying and making music. That’s exactly why you should read this book.

———

Like this review? For more reading recommendations, sign up for my newsletter.

Published by